How Long Does It Take Beef to Get to Market

Finishing Beef Cattle On The Farm

By Paul Beck, David Lalman

- Jump To:

- Selection

- Full general Facility Considerations

- Finishing Options

- Forage Finishing

- Grain Finishing in Solitude

- Grain Finishing On Pasture

- Live Weight to Retail Cuts

- Postmortem Aging Effects on Beef Tenderness

Rural landowners ofttimes are interested in raising livestock to slaughter for personal consumption, local marketing or for normal commodity markets. Advantages to raising your ain beef include having control over calf quality and choice of how the calf is finished out. Calves can be finished on grass, grain and grass, or high concentrate diets. In that location are disadvantages to consider when fattening your ain beef. Disadvantages may include the need to buy a calf, extra labor for feeding, sufficient land set aside for forage-finishing, purchasing and storage of expensive feedstuffs for grain-finishing, or purchasing freezers to shop the beef after slaughter. Calves besides can get sick and may crave veterinary attention, and owners must realize the longer the ownership, the more risk of decease losses due to injury or illness. This fact canvass covers facility and dogie selection, feeding options and slaughter considerations for finishing calves on the subcontract. For more in-depth information on diet, health and growth promoting compounds see AFS-3302 An Introduction to Finishing Beef.

Selection

Calves selected for farm-raised beef vary in type. Budget, marketing niches and end product goals will determine the blazon of calf that works best. Pocket-sized-framed dairy calves, like Jersey calves, tin can have exceptional meat quality; however, percent retail production and size of cuts, similar ribeye steaks, will be fairly modest. A Large-framed, heavy-muscled beefiness brood volition have very skilful cutability (high percentage retail product) but calves of this type can take longer to accomplish maturity, will probable exist slaughtered prematurely and freezer space may exist inadequate to store all the cuts. Calves of beef breeds that are moderate-framed and early on maturing with good muscling are ideal for most farm raised beefiness programs. Producers that desire greater lean may desire calves of traditional Continental breeds like Charolais and Limousin; whereas, producers that desire the flavor and juiciness of steaks with more marbling (intramuscular fat that determines USDA Quality Course) may prefer calves of predominately English language breeding such equally Hereford, Red Angus, Black Angus or Shorthorn. Finishing calves with more than than 25% Brahman influence can tend to reduce cutability and tenderness.

Bulls should be castrated early in life, preferably at nativity or by three months of age. Steaks from intact bulls can be bacteria and tougher than steaks from steers. Ambitious action of group-fed bulls tin become a handling issue as well as increased chances for animal injury and bruising. Heifers make good subcontract-raised beef candidates. Heifers often are kept for breeding, and at the cease of the breeding season, any heifer that did non become pregnant can exist easily finished for slaughter. Because they are before-maturing, heifers generally fatten quicker at a lighter bodyweight and have a slightly poorer feed conversion ratio than males.

Full general Facility Considerations

Shade and current of air breaks. Finishing (forage- or grainfinishing) and marketing goals (personal use or sale) will determine the land and facilities needed. Whether finishing calves on pasture or in dry lot confinement, calves volition be more than comfy if they take access to shade during summertime and a air current break during winter. Calves may grow fairly without shade or a wind break during role of the twelvemonth, but shelter from the elements is necessary when weather exceed the animal'due south thermo-neutral zone. The necessity for admission to shade and wind break may be a personal preference to the level of animal comfort desired and marketing or may be a necessity depending on the environment. If the goal is to market beef locally, buyers may exist interested in subcontract tours to see where the beef was produced. Buyers of locally grown beef are making their ownership decision based in part on their perception of how calves should be reared and if calves don't have access to summertime shade or winter shelter, someone will eventually brand information technology a betoken to ask.

Treatment facilities. Cattle handling facilities at a minimum should include a catch pen with a lane and headgate to be able to vaccinate, treat illness, castrate and dehorn. Poorly maintained working facilities tin be a source of injury and bruising that may cause product loss. Walk through working facilities and look for possible points of injury, such as protruding confined, bolts or nails.

Feed storage and treatment. Wasted feed due to poor storage and handling techniques increases the toll of producing beef. Feeds should be stored in a dry location to reduce the chances of molding. Feed storage facilities demand to be kept clean to keep pests (rodents and insects) at a minimum. It is essential feeding rates be managed to limit build upwardly of uneaten feed. Feed troughs as well should exist kept make clean to minimize leftover feed spoilage and buildup of uneaten portions due to mixing fresh feed with spoiled feed in troughs.

Hay used in fodder-finished beefiness programs should be loftier in quality. Storing hay under UV-protective tarps or in barns will reduce storage waste. Feeding round bales in protected rings that either keep the bale centered or have a metal canvass around the bottom minimize feeding waste matter (see the fact sheets BAE-1716 Circular Bale Hay Storage for more in depth information on hay storage losses and PSS-2570 Reducing Winter Feed Costs for more data on improved hay utilization)

Finishing Options

Fodder- versus Grain-finishing. The objective here isn't to beginning a grass- or grain-finished debate; in that location is room for both in a local farm-raised beefiness market. Information technology is of import to understand common characteristics of fodder- versus grain-finished beef when deciding which option is best for beef produced on-farm for personal apply or marketing. In general, the typical beef consumer of the U.S. prefers the season of grain-fed beef. By comparison, ground beef from cattle finished on forage has been characterized as having a 'grassy' flavor. Grass-fed ground beef besides can have a cooking olfactory property that differs from grain-fed beef. The visual appearance of the fatty of grass-fed beef can be more than yellow in colour due to carotenoids in comparing to grain-fed beef fat, which appears white.

An overview of 23 published studies from 1978 to 2013 showed that cattle finished on pasture gained 1 pound less per day than cattle fed loftier-concentrate diets in confinement (1.55 vs two.54 pounds per day.) Provender-finished cattle were finished at a lighter weight (~950 lb pounds) than grain-finished cattle (~1,100 pounds) and dressed at a lower per centum (56% vs 60%). Fodder-finished cattle had 0.ii inches of dorsum fat vs 0.5 inches for feedlot finished and as a outcome are leaner when delivered for slaughter compared to grain-finished cattle. Bacteria beef is generally scored by sense of taste panelists as being less tender and less juicy compared to fatter beefiness. So, the health-conscientious consumer seeking forage-raised beef is usually willing to have trade-offs of flavor, tenderness and juiciness for a leaner beef that may contain a greater proportion of eye-salubrious fats. Whereas, other consumers may continue to seek the grain-finished beef characteristics, but want to support local sources of grain-fed beefiness.

Fodder Finishing

Provender finishing capitalizes on the beef animal's ability to convert fodder into musculus protein through the assistance of microbial breakdown of forage celluloses in the rumen. Since cattle are naturally grazing animals, some consumers seek out beefiness from cattle reared in their "natural environment". The first challenge to forage-finishing is having a sufficient area of grazeable state. Forage dry matter intake is thought to exist maximized when forage allowance is kept above 1,000 pounds per acre. Forage-based systems may require 1 acre or up to 10 acres per calf depending on fertilization, weed control, seasonal forage productivity, forage species and management. Fifty-fifty with good fodder direction, hay is often needed for two months to four months during winter. To sustain good dogie growth rates and reduce the number of days required to finish calves on a forage-based system, high-quality hay should be offered when pasture grasses are limiting. Supplementation with concentrate feeds such as soybean hulls may be needed to boost gains and permit for fat deposition when hay or pasture is moderate to low quality. Soybean hulls are recognized by the American Association of Feed Control Officials as a roughage source and is canonical for grass-fed beef claims past the USDA. Other organizations set differing standards for definition of 'grass-fed' these organizations offer marketing alliances and certification, if you are (or desire to exist) a member, you tin refer to their guidelines for animal care and approved direction and nutrition.

The second limitation to provender-finishing is dogie growth response. As provender quality, forage quantity and ecology temperatures fluctuate throughout the year, average daily proceeds may range from seasonal highs of greater than 2.0 pounds per day to seasonal lows of 0.5 pound per twenty-four hour period or less. As a result, calves grown in forage-finishing systems often are slaughtered before they reach the aforementioned degree of fatness of grain-finished cattle. Forage-finished calves often will be slaughtered near 1,000 pounds live weight. Information technology will take over a yr (367 days) to grow a 500-pound calf to 1,000 pounds if its boilerplate daily weight proceeds is 1.5 pounds per 24-hour interval. Some extensive forage-finishing systems may require a longer duration for calves to reach slaughter weight if fodder quality and quantity restrict growth to no more than 1 pound per day.

Intensive jump and summer forage-finishing systems can exist accomplished with mixtures of forages like legumes, perennial grasses, annual grasses and brassicas. Research at Clemson University compared forage species for finishing calves on pasture during late-spring and summertime months. Calves used in the written report were grown the previous winter on rye/ryegrass and fescue. Finishing forages studied included alfalfa, bermudagrass, chicory, cowpea, or pearl millet. Pastures in this study were stocked at i.7 acres per calf with the exception of pearl millet which was stocked at 0.8 acres per calf. The amount of pasture forage maintained during the study ranged from 1,300 pounds to 2,500 pounds per acre. Tabular array i is a summary of the study results.

Steers grazing bermudagrass pastures gained 1.7 pounds per twenty-four hour period, while steers grazing alfalfa (two.eight pounds per ), chicory (2.5 pounds per day) and cowpea (1.9 pounds per ) gained more rapidly and had greater backfat thickness at slaughter. Steers grazing pearl millet only gained 1.2 pounds per day and had the least backfat at slaughter. Amongst the finishing systems, fatty acid composition tended to be similar and the ratio of the polyunsaturated fats to saturated fats was similar. In this study, all treatments had shear force values that would be considered at or below the threshold for consumer accustomed tenderness.

Inquiry in Georgia (Table 2) compared forage-finishing on toxic fescue and not-toxic, endophyte-infected tall fescue starting in the fall and ending in the spring for a 176-day grazing period. The stocking rate of the toxic fescue was ane.5 steers per acre and the stocking rate of the non-toxic fescue was one steer per acre. When fescue became limited during winter months (Jan and February), calves were grouped into a single pasture and were fed bermudagrass hay. In general, toxic fescue reduced growth charge per unit which resulted in lighter carcass weights, but tenderness and consumer panel attributes were not enhanced past non-toxic fescue. WarnerBratzler shear force for the steaks from is trial were much higher than the threshold level of adequate tenderness (ten pounds) and would be considered tough by manufacture standards. When carcasses were aged for fourteen days, shear force values decreased to 10 pounds, a level that would be on the upper limit of threshold WBSF values considered acceptable for tenderness by consumers (Realini et al., 2005).

Table 1. Growth and carcass attributes of calves finished on unlike forages during tardily-spring and summertime (adapted from Schmidt et al., 2013).

| Alfalfa | Bermudagrass | Chicory | Cowpea | Pearl Millet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grazing days per acre | 68 | 89 | 55 | 46 | 112 |

| Offset weight, lbs | 893 | 1,047 | 931 | one,058 | one,052 |

| Cease weight, lbs | 1,184 | i,274 | 1,137 | 1,221 | 1,155 |

| Average daily gain, lb/24-hour interval | 2.8 | 1.7 | 2.five | 1.9 | ane.2 |

| Carcass weight, lbs | 711 | 719 | 675 | 752 | 664 |

| Backfat thickness, inches | 0.30 | 0.ii | 0.thirty | 0.27 | 0.xviii |

| Dressing, % | 60.0 | 56.4 | 59.iv | 61.6 | 57.5 |

| Quality grade | three.five | 3.eight | 3.2 | 4.iv | 3.viii |

| Warner-Bratzler shear force, lbs | 8.eight | ten.6 | 9.9 | 8.8 | nine.9 |

| Consumer preference, % | 40% | v% | ten% | 20% | 25% |

Quality grade code: iii = Low Select, iv = High Select, v = Depression Pick (higher is associated with greater fat and less lean) Warner-Bratzler shear strength (lower is associated with greater tenderness, all treatments were at or beneath the threshold of 10 more often than not recognized equally tender past consumers)

Table 2. Growth and carcass attributes of calves finished on toxic and not-toxic, endophyte-infected fescue from fall through bound (adjusted from Realini et al., 2005).

| Toxic Fescue | Non-toxic Fescue | |

|---|---|---|

| Terminate weight, lbs | 906 | 992 |

| Carcass weight, lbs | 491 | 541 |

| Backfat thickness, inches | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| Dressing, % | 54.ii | 54.5 |

| Quality grade | 3.0 | 2.8 |

| Warner-Bratzler shear force, lbs | 13.2 | 15.iv |

| Consumer console – Chewiness score | ii.8 | 3.7 |

| Consumer panel – Juiciness score | 2.seven | 2.iv |

Quality grade code: 3 = Low Select, four = High Select, 5 = Low Choice (higher is associated with greater fatty and less lean) Chewiness score: 1-to-5 scale with i beingness most desirable and 5 being least desirable. Juiciness score: 1-to-5 scale with 1 existence to the lowest degree desirable and 5 being almost desirable.

A study at the University of Missouri examined the upshot of adding either reddish clover or alfalfa to a fescue based foragefinishing system for a 3-month finishing period from tardily March through July. The amount of legume in these systems was 38% in the alfalfa system and xvi% in the blood-red clover system. Final weight of calves did not differ between the fescue and combined legume response and averaged 1,035 pounds. Calves in the alfalfa system were fifty pounds heavier at the end of the study compared to the red clover arrangement, which could had been influenced by difference in legume forage availability. The fatty acrid limerick of fat taken from the loin musculus did not differ among provender types.

Another report at Clemson (Table 3) compared a legume system to a grass system with or without supplemental corn fed at 0.75% body weight. The legume systems utilized alfalfa and soybeans while the grass system utilized non-toxic fescue and sorghum-sudangrass. While corn supplementation provided some beneficial responses, these responses were contained of forage organisation; therefore, the difference in forage arrangement is summarized in Table 3. Forage type had little influence on fat acid limerick; withal, greater fat soluble vitamin content was detected in the loin muscle of grass finished beefiness in this written report.

As a general summary, the forage organisation called will kickoff be dictated by fodder species that are already present. Replacing forages with alternative species or interseeding with complementary forages will be dictated by soil type, topography, and soil fertility. Calves tin be forage-finished on grasses, legumes or combination thereof. Electric current research results do not suggest whatsoever unmarried system is platonic based on carcass quality and consumer sensory comparisons.

Grain Finishing in Confinement

While ruminants take the distinct ability to catechumen cellulose into musculus poly peptide through ruminal microbial fermentation, at that place remains a history of fattening cattle on feedstuffs other than fodder long before the institution of the modern confinement feedlot manufacture. Early on fattening in America included root crops, "Indian corn", tree fruits and brewing and distillery mash. Confinement feeding in early America likewise was a mechanism to concentrate manure for fertilizer. Unlike fodder-finishing, grain-finishing requires less land. Depending on soil type and topography, every bit little as 150 square feet per calf of pen space with a feed and h2o trough is sufficient. Sometimes, locally grown beef producers may let a much larger surface area to go along grass cover in the lot instead of allowing the pen to go a clay lot.

Table three. Growth and carcass attributes of calves finished for 98 to 105 days in a grass organisation or a legume organisation (adapted from Wright et al., 2015).

| Grass System | Legume System | |

|---|---|---|

| End weight, lbs | 1,142 | 1,166 |

| Carcass weight, lbs | 669 | 697 |

| Backfat thickness, inches | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| Quality grade | 4.5 | four.seven |

| Consumer panel – Tenderness score | ii.eight | 2.eight |

| Consumer panel – Juiciness score | 2.0 | one.nine |

Quality class code: three = Low Select, 4 = High Select, 5 = Low Choice (higher is associated with greater fat and less lean) Consumer panel scores converted to i-to-5 calibration with 1 being least desirable and 5 being most desirable.

When finishing calves in groups, 22 inches to 26 inches of linear trough infinite per calf is needed when all calves will exist eating at once on the same side of the trough. Grain diets are much drier than pasture diets and when calves are fed in confinement, they are normally watered from a trough. Keeping the water trough make clean is extremely important. A low in water intake can crusade a reduction in feed intake and slow growth rate. During hot weather, a calf near finishing weighing i,000 pounds or more tin can consume more twenty gallons per mean solar day (for more than on h2o requirements of finishing calves run into AFS-3302 An Introduction to Finishing Beefiness.)

Many associate grain-fed beef with corn-fed beef. From 2005 through 2011, corn use for ethanol grew to the point the total apply for ethanol reached that of feed and residue use. A feedlot finishing nutrition today may contain 6% to 12% roughage, up to 50% byproduct feeds such as distiller's grains and corn gluten feed and cereal grains (mostly corn) representing 50% or more of the finishing diet.

Mimicking feedlot diets may non be applied when finishing calves on-farm; however, similar steps used in the commercial feeding industry should exist adopted including:

- Calves should be transitioned from a roughage diet to the final high concentrate nutrition over a three-week period. This is called a step-up program.

- Feed calves at to the lowest degree twice per day when the final diet does not contain built in roughage or is not formulated to be self-fed or self-limiting.

- Include 10% to 15% roughage in the final diet for increased rumen health and reduced acidosis.

- Feed calves a balanced diet (poly peptide, minerals, mineral ratios and vitamins).

- Accommodate feed amount as calves grow.

Consult with a nutritionist to develop a ration based on locally bachelor ingredients or use a commercial finishing ration. Some feed mills offer "bull evolution rations" that can as well exist used as a decent finishing ration. These "bull development rations" sometimes include enough cottonseed hulls and byproduct feeds that boosted roughage is not needed.

In addition to distiller's grains and corn gluten feed, other byproducts such as soybean hulls may be used in finishing diets. Soybean hulls has an estimated feed value of 74% to lxxx% of corn; whereas, dried distiller's grains has demonstrated a 124% feed value of corn. There is trivial indication that feeding byproduct feeds changes the marbling of cattle as long equally free energy density requirements are met for fat deposition. Enquiry results indicate less intensively processed grains (ie feeding whole corn or rolled corn) may result in higher marbling than intense processing methods normally used in commercial finishing operations (ie loftier moisture corn or steam flaking). This is thought to be due to the site of starch digestion being shifted to the small-scale intestine with less intensive grain processing supplying more glucose to drive marbling.

Feeding Concentrate and Roughage Separately. Feed milling, mixing and delivery take upwardly much of the daily activities in commercial scale feedyards. This is an equipment-intensive operation with large capital outlays necessary for the feed mill and equipment for feed commitment. On a smaller scale, large investments in feeding systems may non be warranted. Delivery of total mixed diets balanced to run across nutritional needs of finishing cattle adds efficiency to large commercial operations that cannot exist matched by smaller-calibration finishing operations. Diets formulated for on-farm finishing also can be based on limit feeding the concentrate portion in the trough while allowing calves to have free choice admission to pasture or hay for roughage. Research (Atwood et al., 2001) comparing intake and performance by fattening calves offered either a 65% concentrate (rolled barley and rolled corn) total mixed ration with alfalfa hay and corn silage providing the roughage or providing all dietary ingredients offered complimentary-choice for self-selection establish that no two animals offered complimentary-pick consumed like diets or selected diets similar to the TMR. The authors concluded gratis-choice nutrition selection was adequate for each private beast to 'run across its needs'. Operation of cattle fed TMR or offered free-pick selection of diets and feed efficiency were like betwixt feeding systems.

More than recent inquiry from Canada (Moya et al., 2011 and 2014) was conducted to compare performance, efficiency and rumen pH of cattle finished on a TMR based on barley grain (85%), corn silage (x%) and protein/mineral supplement (5%) vs offered concentrate and roughage separately for costless-choice selection. All cattle were adapted to the TMR diet and the free-pick diets were available over the 52-day experiment. During the 52 days, cattle selected diets with increasing barley, reaching 70% to 80% of their cocky-selected nutrition, merely even with the increasing barley in the nutrition, ruminal pH was like to calves fed the TMR in the first experiment (Moya et al., 2011). In the first ii-week period calves consumed approximately 75% barley grain, increasing to eighty% in weeks 3 and four, and to 85% in weeks v through 7; the boilerplate selected diet for cattle offered barley and corn silage was 80% barley grain and 20% corn silage. While in the 2nd experiment, calves offered costless- choice access to corn silage and barley grain cocky-selected diets that were 86% barley and 14% corn silage without altering ruminal fermentation characteristics and blood profiles (Moya et al., 2014). As with previous experiments, cattle given costless-option access to self-select diet ingredients in both experiments performed similarly to cattle fed TMR. These inquiry ended cattle can effectively self-select diets without increasing the risk of acidosis and maintain production levels for growth and feed efficiency.

If a producer wants to utilize a free-choice, self-pick feeding organization where roughage and concentrate are fed separately, a few management steps should exist taken.

- A step-up period of increasing grain availability is a must, cattle should be acclimated to the high concentrate diets during at least xx days;

- Employ palatable, loftier-quality hay, silage or roughage source;

- Limit-feed concentrate and practice practiced feed bunk direction;

- If limit-feeding hay – feed hay beginning, then provide the concentrate portion of the diet;

- Concentrate blends of grains and byproduct feeds are safer than providing grain simply;

- Think well-nigh safer concentrate feeding alternatives—feeding whole corn is safer than finely basis corn and tin be an option for growing and finishing calves

Grain Finishing On Pasture

Hybrid systems accept been studied as an alternative to high-concentrate total mixed rations fed in confinement. These systems apply the roughage supplied by pasture along with additional energy from supplemental concentrates. They may non encounter the requirements to meet 'grass-fed beef' claims by the USDA, but do provide free-pick access to pasture.

Cocky-fed supplements on pasture tin be another arroyo to finishing cattle. Research at Iowa Country University (Table 4) examined self-fed dried distillers' grains with solubles mixed 1:1 with either soybean hulls or basis corn. In addition, a mineral that helped balance the calcium-to-phosphorus ratio and contained monensin to improve charge per unit of proceeds was added at 4% of the mix. The calves were stocked at approximately 2.25 calves per acre of predominately tall fescue pasture. Estimated contributions of self-fed concentrate and pasture to the full dry matter feed intake in this study was 80% and 20%, respectively. The study did non written report any bug with digestive upset with cocky-feeding.

Ii studies were conducted at the Academy of Arkansas (Apple tree and Beck, unpublished data). In the first trial, calves from bound or fall calving herds were either sent to a Texas Panhandle feedyard for finishing every bit yearlings following a stocker program or kept at the dwelling operation and supplemented with 1% of bodyweight per caput per day with a grain/grain byproduct supplement until slaughter. Steers finished conventionally in confinement gained 4.4 pounds per day, while steers fed concentrate supplement on pasture gained ii.5 pounds per twenty-four hours. Although the finishing period on pasture was thirty days longer on the boilerplate, steers finished in the conventional feedlot were 128 pounds heavier at slaughter and dressing percentage was higher 62.v% vs 60.six% for Conventional and pasture, respectively). Conventionally finished cattle were 86% Choice while pasture finished were 78% Select quality grade.

Table 4. Growth and carcass attributes of calves finished on self-fed concentrates (adapted from Kiesling, D.D. 2013).

| Distillers' grains plus solubles:corn [50:50] | Distillers' grains plus solubles:soybean hulls [fifty:50] | |

|---|---|---|

| Average daily gain, lbs | 3.four | 3.3 |

| End weight, lbs | 1,302 | 1,291 |

| Carcass weight, lbs | 816 | 807 |

| Dressing, % | 62.6 | 62.5 |

| Backfat thickness, inches | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| Quality Class | 5.0 | five.0 |

Estimated concentrate intake was eighty% and pasture intake 20%. Quality grade code: 3 = Depression Select, 4 = High Select, v = Low Pick

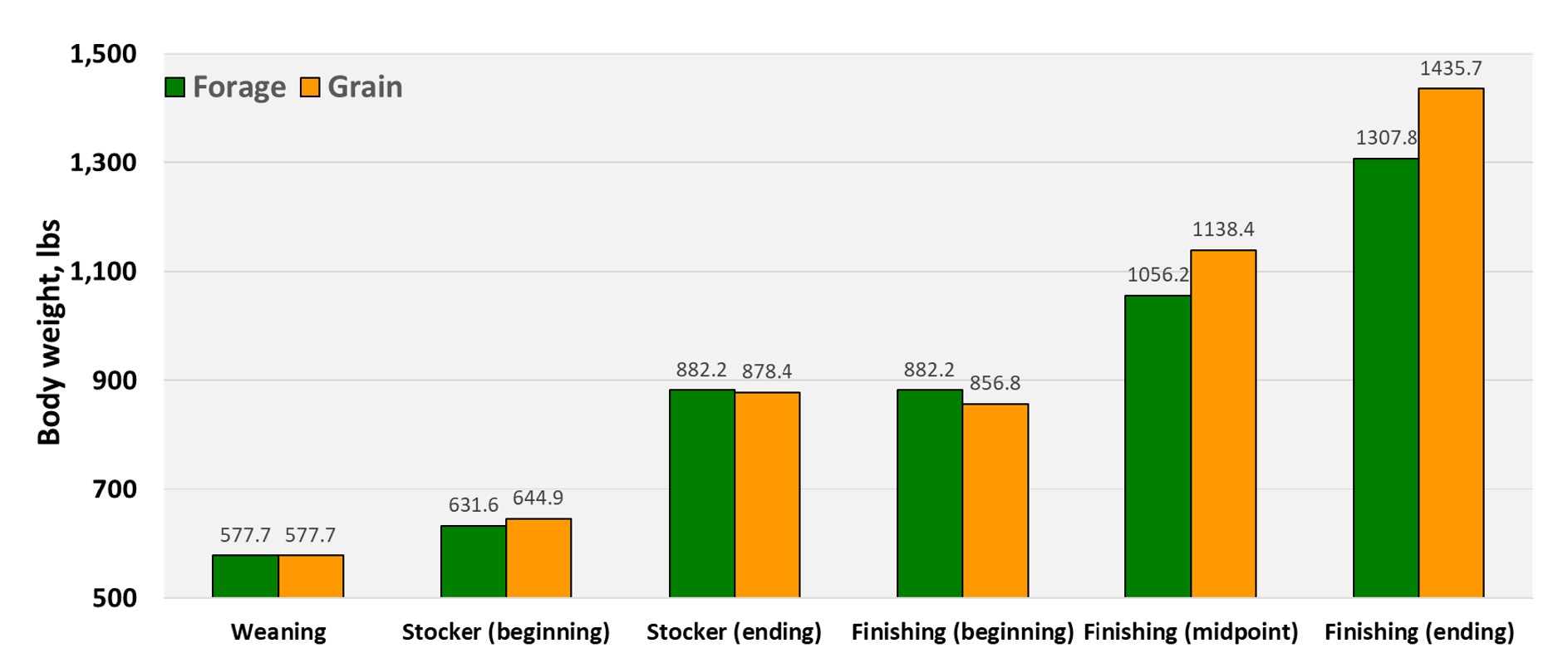

Figure 1. Issue of finishing on pasture (Forage) with 1% of bodyweight concentrate supplement daily or conventional finishing (Grain) on bodyweight of steers.

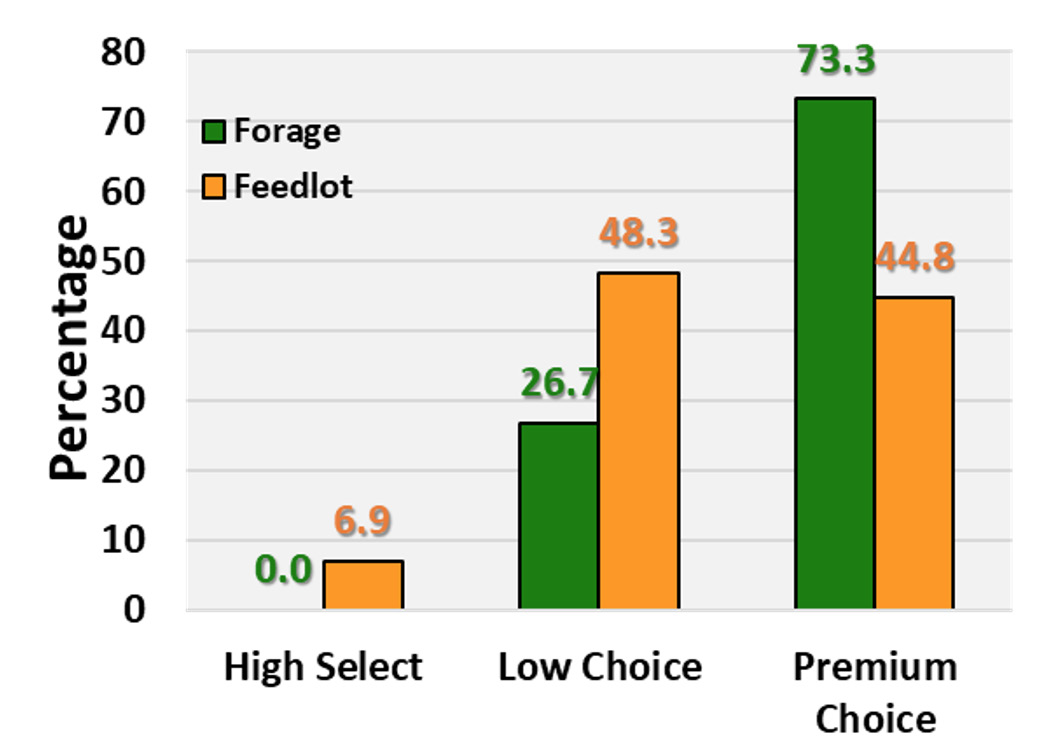

In the next trial, 60 calves were either finished in conventional Texas Panhandle feedyard or were kept on pasture with a grain/grain byproduct concentrate supplement fed at 1.5% of bodyweight daily. Steers finished on pasture with supplement gained 3.6 pounds per day (vs 4 pounds per day for conventional) and were fed 40 days longer than conventional steers, merely were still 40 pounds lighter at slaughter. But, hot carcass weights (836 for pasture vs 854 for conventional) were not as impacted as in the previous study, fat thickness was similar for the two treatments (0.62 inches for pasture vs 0.52 inches for conventionally finished) and dressing percentage was too like (63% for pasture and 62.5% for conventional). In this experiment, the cattle finished on pasture with supplement were 100% Choice, with 73% being Premium Choice; while the Conventional steers were 93% Selection, with 45% being Premium Choice. This inquiry indicates acceptable carcass performance can exist obtained with limited free energy supplementation on pasture.

Figure ii. Effect of finishing on pasture (Forage) with 1.v% of bodyweight concentrate supplement daily or conventional finishing (Grain) on carcass quality grade.

Live Weight to Retail Cuts

The final corporeality of retail cuts produced from a alive calf will exist afflicted past frame, muscle, bone, fat cover and gut capacity/fill. The offset measure out of yield is dressing per centum which is the percent of carcass weight relative to live weight. Dressing percentage tin can range from 58% to 66%. A 1,300-pound steer that yields a carcass weighing 806 pounds would have a 62% dressing percentage. A second measure of yield is retail product. The USDA Yield Form is a numerical score that is indicative of retail product. A calculated Yield Class is determined from hot carcass weight, fat thickness at the 12th rib, ribeye surface area and the combined percentage of kidney, pelvic and middle fatty. Per centum of retail products can be calculated from these same measurements. Percent retail product may range from 45% to 55%. A 1,300-pound steer at Yield Class 3 would have a retail product per centum of 50% which would yield almost 650 pounds of retail production. If two individuals purchase a side of beef each, they each can expect 325 pounds of retail production. The yield of retail product will consist of approximately 62% roasts and steaks and 38% ground beef and stew meats. And then, a single side of beef that yields 325 pounds of retail product as well would yield approximately 201 pounds of roasts and steaks and 124 pounds of ground beef and stew meat.

Postmortem Aging Furnishings on Beef Tenderness

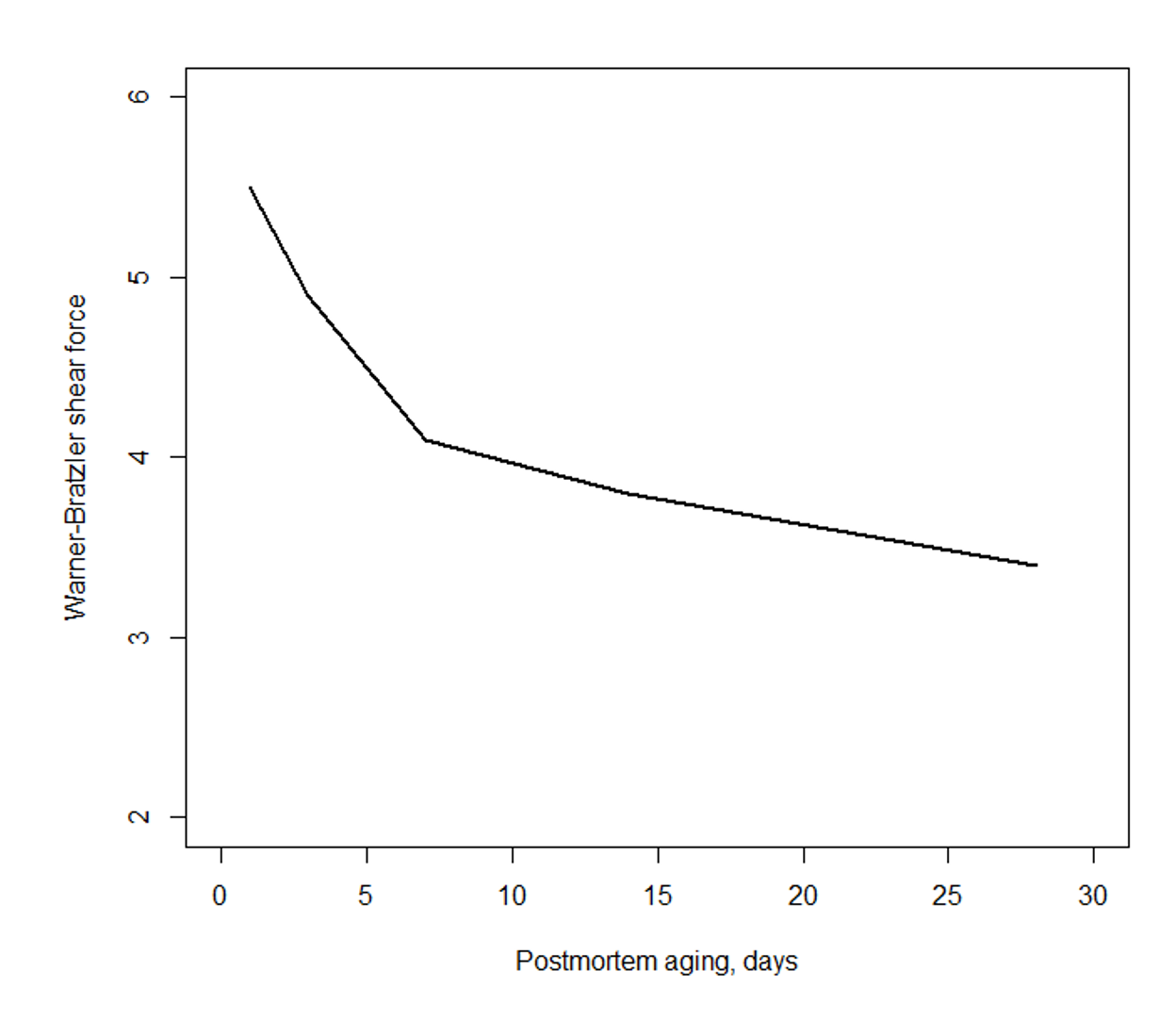

Figure 3 illustrates the benign effects of crumbling on tenderness as measured in a laboratory as Warner-Bratzler shear forcefulness. This naturally tenderizing process ceases once meat is frozen. When possible, postmortem crumbling should be at least seven to 15 days to accomplish threshold shear force values for consumer acceptable tenderness of 8.3 pounds to x pounds (3.viii kg to 4.6 kg). Aging across this timeframe is often restricted due to the processor's libation space, but could event in further improvements in tenderness.

Figure 3. Effect of aging on forage-finished beef tenderness equally determined by Warner-Brazler shear force (adapted from Schmidt et al., 2013).

Was this information helpful?

YESNO

Source: https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/finishing-beef-cattle-on-the-farm.html

0 Response to "How Long Does It Take Beef to Get to Market"

Post a Comment